Think about sitting around a campfire. The fire emits a measurable level of heat, and the nearer you sit to it, the hotter the fire feels. If you are farther from the fire, the heat is less intense. This simple example can explain common earthquake measurements – magnitude and intensity – and what these earthquake scales mean.

Richter Scale

Consider, once again, the campfire. This temperature is measurable and absolute. When an earthquake occurs, the Richter scale measures the magnitude of the earthquake at its epicenter. The Richter scale was developed in 1935 as a way to quantify the strength of earthquakes. It is a logarithmic scale based on the amplitude of the waves recorded by seismographs. A logarithmic scale means a magnitude increase of 1 relates to an energy increase by a factor of 10. An earthquake measuring a 4.0 on the Richter scale is 10 times as strong as a 3.0!

Earthquake seismograph at Weston Observatory at Boston College, Weston, Massachusetts.

Modified Mercali Intensity Scale

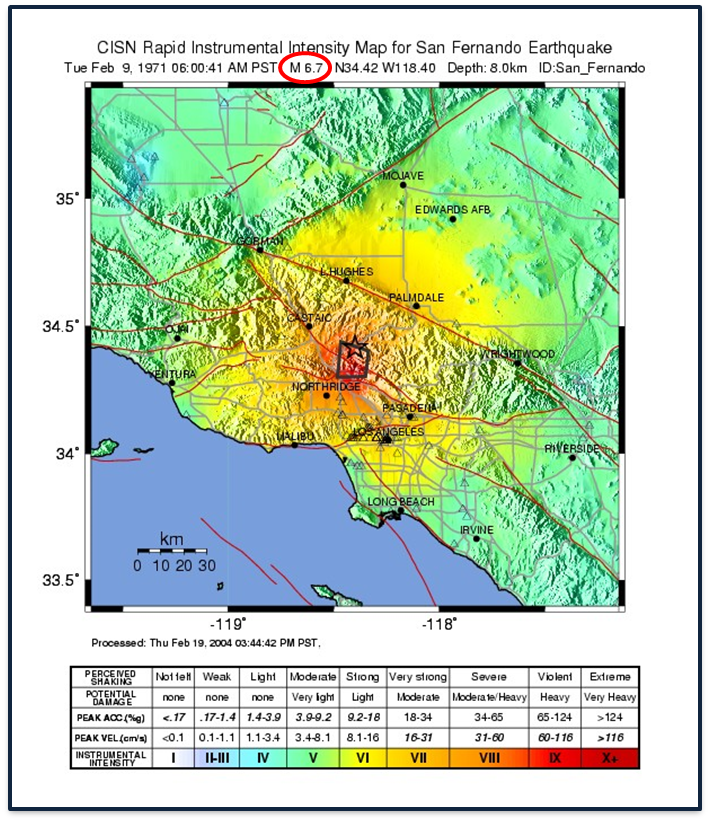

Now, you know the closer to the campfire you sit, the hotter the flames feel on your skin. This generally holds true with earthquakes as well. Typically, the nearer the epicenter the stronger the ground shaking you would feel; however, there are other factors that affect the intensity of the earthquake you feel at your location. The type of earthquake, bedrock the shockwaves traveled through, and amplitude of the shockwaves from the earthquake are a few of these factors. The intensity you feel is measured on a scale called the Modified Mercali Intensity Scale (MMI). The MMI scale ranges from “Not Felt” and “Weak Shaking” up to “Violent” and “Extreme” with well-built structures suffering damage.

USGS earthquake map and intensity scale for 1971 San Fernando Earthquake (Magnitude – red-circled, epicenter – star, Modified Mercali Intensity scale – table)

Other Scales Around the World

While the Richter scale is widely known and the MMI scale is used in the United States, there are other magnitude and intensity scales in use around the world. The Japanese Meteorological Agency uses a separate calculation for shallow earthquakes (depth < 60km) which has been shown to be reasonable when the magnitude is 4.5-7.5; however, this magnitude measurement has historically underestimated larger magnitude tremors. Additionally, Japan and Taiwan use the Shindo intensity scale which has significant correlation to the MMI scale. During the middle to late 20th century, the USSR, East Germany, and Czecholsovakia established and utilized the Medvedev-Sponheuer-Karnik scale (MSK) to evaluate shaking and effects from earthquakes. This scale was built upon in the 1990s by the European Seismological Commission as they shifted to implement the European Macroseismic Scale for European countries. The MSK scale continues to be employed in Russia, India, Israel, and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

You can read more about some of these other scales here:

JMA Shindo intensity scale: https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/en/Activities/inttable.html

MSK Scale: https://www.gktoday.in/gk/various-earthquake-scales/

Sources:

https://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/topics/mercalli.php

https://www.japan-talk.com/jt/new/why-japan-doesnt-use-magnitude-for-earthquakes

One Comment