RedZone has highlighted five lesser-known areas where homeowners have increased wildfire risk

- Mid-slope areas

- Areas Adjacent to Wildland Fuels

- In the Ember Zone

- In Urban Canyons

- Proximity to Highway Grade

Mid-Slope

Mid-slope is an area commonly thought of as midway up a hillside, in this case, were using in terms of how it’s viewed in a wildfire-prone area. Homes are built and bought in these areas which are one of the least safe places to be during a wildfire. Typically, wildfires burn up a slope faster and more intensely than along flat ground. The steeper the slope the longer the flame lengths and faster-moving the fire. Any slope can potentially increase the amount of heat a structure will be subject to during a wildfire, enhancing wildfire risk.

Not only is a home in this area more at risk, fire-fighting operations there are increasingly dangerous as well. Just one example from a few years ago, a mid-slope fatality is now a lesson learned from the Coal Canyon Fire in Fall River County, South Dakota. Essentially, firefighting orders will not allow for crews to work mid-slope assignments above a fire without large defensible space or a barrier/structure. Due to the adherent wildfire risk, both Fire Prevention Divisions and Underwriting guidelines suggest an aggressive vegetation modification and maintenance plan if the home or business is located mid-slope or at the top of a steep slope. The insured must also be aware of building materials used, especially if the structure is set back less than 15 feet.

A worrisome home built along a mid-slope road near Lake Elsinore, CA

Adjacent to Wildland Fuels

It is well known that neighborhoods in or bordering the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), have a greater risk for impact by wildfire. In depth studies show in those neighborhoods, homes on the outskirts have a higher risk than those located more interior. One of the main reasons why homes bordering the natural vegetation are at a higher risk of ignition is the lack of any buffer between the structure and the surrounding vegetation. These homes are located in extremely close proximity to the natural vegetation of the surrounding area and, thus, vulnerable to more direct flame impingement. This effect is exacerbated if the individual property owner has not taken the time to prepare his or her land for the occurrence of a wildland fire threatening their property.

Conversely, homes within the development have defensive barriers surrounding them. The inner structures have roads separating them from the structures bordering the surrounding natural vegetation and topography. These interior homes also are more likely to have moisture-rich vegetation such as, lawns, gardens, and manicured brush, making for more difficult sources of ember ignition.

The Sage Fire, near Simi Valley, CA back in 2016 is a good example of the homes located on the outskirts of these neighborhoods being at higher risk than the ones located within. As the fire made a push upslope to the ridgeline, it also spread out following property barriers on the outskirts of the neighborhood. The homes bordering the flame front were at a very high risk of the fire finding an ignition source to endanger it. Homes deeper into the neighborhood were less vulnerable because of the barriers aforementioned and those provided by the outlying homes. Fortunately, no homes were impacted due to a small fire break placed in the vegetation immediately adjacent to the properties.

2016 Sage Fire burned between dense neighborhoods in Simi Valley, CA

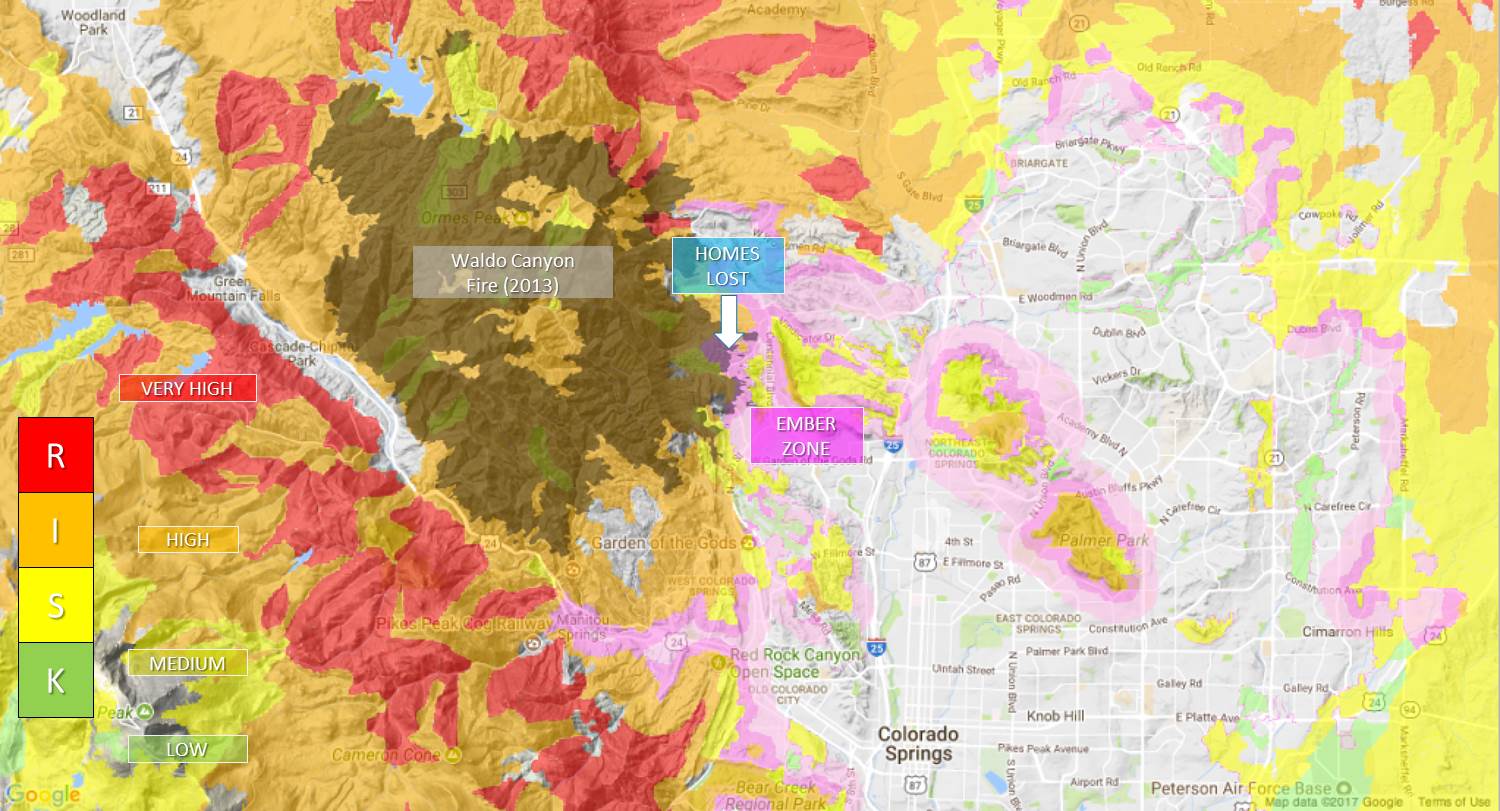

In the Ember Zone

The “Ember Zone” can be defined as the area that could potentially have ember fall out due to a fire burning in the near vicinity. This zone can be up to a mile away from an active wildfire, depending on the size of the fire and wind speed. These embers are thrown from the fire and carried by the wind in the direction that it is blowing. If embers are hot enough and land in a receptive fuel bed, this can lead to an ignition of a spot fire ahead of the active fires edge. Spot fires caused by embers pose a threat because they sometimes go unnoticed for an extended period of time by fire personnel. This is especially the case when spot fires ignite at a distance away from the head of the fire. The longer the new start has to become established, the harder it is for firefighters to respond effectively to save structures in the path of the newly ignited spot fire.

Another way the Ember Zone can pose a threat to a homeowner would be the process of the embers being blown into uncovered vents on the home, or an ignition source located near or inside the home. Either could result in a fire starting in the structure itself. An example of how the Ember Zone proved catastrophic is in the Waldo Canyon Fire near Colorado Springs, Colorado. This fire experienced a drastic wind shift during the second operational period. This wind shift threw embers upwards of half a mile in the direction of the structures located in Colorado Springs. 346 homes were lost in the tragic fire of 2012, some of these were a direct result of ember fall out. Others were lost because of their direct contact with the active fires edge.

Embers contributed to many of the 346 homes lost on the Waldo Canyon Fire in 2013 in Colorado Springs, CO

In Urban Canyons

Southern California is known for its mix of wild canyons in between urban, even historic, developed neighborhoods. These canyons offer convenient hiking trails and a natural landscape that is unique in an urban environment. But, they also provide heavy fuels, steep slopes, and human activity that lead to dangerous fires that often threaten homes. Many urban canyons have homes adjacent to the canyon walls and even a relatively small wildfire can threaten many homes in these environments.

Examples of wildfires starting in urban canyons:

- Poinsettia Fire – Destroyed 22 homes and burned 400 acres. Fire started on a golf course and rapidly spread through urban canyons.

- City Heights Fire – Less than 2 acres, but came within a few feet of homes within an hour of a fire being reported.

- Manzanita Canyon – Several instances of homeless cooking fires getting out of control in the canyon.

Homes with little to no defensible space in a San Diego Urban Canyon

Proximity to Highway Grade

If you are considering buying a home near a highway grade, you may get a nice view but could also be at higher risk for wildfires. Steep highway grades add additional complexity and stress on vehicles. Traffic collisions, mechanical failure, electrical issues, and fuel system malfunctions can cause vehicle fires that can extend to vegetation as well. According to the National Fire Protection Association, there is an average of 152,000 vehicle fires per year in the United States. Poorly maintained vehicles, put under stress while climbing up or braking down grades, can break down. As the driver pulls over to the shoulder or off the road entirely, catalytic converters, brakes, dragging exhaust parts, or cigarette butts can ignite dry grasses along a highway. Also, improperly loaded trailers can drag chains; creating sparks that can ignite grasses as the vehicle passes by unknowingly. All of these things can happen at any point along a highway. Added stress and heat generated by steep grades increases the likelihood of a fire starting and therefore wildfire risk.

The steep grade along Interstate 5 on the north end of “the Grapevine” between California’s Central Valley and Los Angeles contributes to large fires in steep terrain and roadside fires that seem to threaten Lebec and Frazier Park every year. [Fire History using #FireMappers]

Examples of large wildfires starting on major highways:

- Blue Cut – Highway 15 along the Cajon Pass. Destroyed 105 homes and burned over 36,000 acres.

- Springs Fire – Highway 101 along the Conejo Grade. Caused by an undetermined roadside ignition. Fire burned 15 homes but threatened 4,000 and burned 24,000 acres. The fire burned until it hit the coast.

- Grade Fire – Ridgewood Grade on Highway 101. Caused by a vehicle fire spreading to grass. Burned 900 acres.

SOURCES:

http://www.fire.ca.gov/fire_protection/downloads/redsheet/Jesusita/JesusitaReviewReport.pdf

https://apps.usfa.fema.gov/firefighter-fatalities/fatalityData/detail?fatalityId=3935

http://www.firesafemarin.org/topography

http://www.readyforwildfire.org/Vehicle-Use/

http://www.nfpa.org/public-education/by-topic/property-type-and-vehicles/vehicles

http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/TechnicalNotes/NIST.TN.1910.pdf