Earlier this week I published some thoughts about the first 24 hours of the October Napa Sonoma Fire Siege. The unprecedented destruction caused by these fires provoked many questions in the emergency world, insurance, and especially the public. We asked our Senior Fire Liaison Doug Lannon his thoughts to questions regarding; 1) Why were so many homes lost, 2) Why are these fires different, and 3) Why did we see so many homes burn to the ground, but some trees next to homes are still standing?

Weather

Northern California and the North Bay had been in Red Flag Warning conditions for several consecutive weeks before the fires, and were still under a Red Flag Warning when the fires began. A severe “Santa Ana” type Foehn wind event coupled with low Relative Humidity and dangerously low fuel moistures were a design for disaster under the circumstances.

- The winds were coming out of the northeast sustained at 40 mph with gusts up to 75 mph

- Relative Humidity was in the single digits (RH below 20%, more receptive to ignitions)

- Hot 80 and 90 degree temperatures contributed to the fuel ignition temperature and fire spread

- During the autumn months, the North Bay temperatures are cooler and many people leave their windows open, making their homes and businesses even susceptible to ember intrusion

Fuels

Following more than five years of drought, the area received almost three times the normal amount of rain last winter and spring, causing two to three times the amount of grass crop and light flashy fuels to grow, but not enough to raise the living fuel moistures in heavy brush and timber to recover completely. Also tree mortality is at an all-time high in the North State.

- Dead fuel moisture sticks were hovering between 1 and 2 (10 is maximum, below 5 is serious)

- Living fuel moisture was at 57% (80% is serious and below 60% is critical), 240% is maximum

- Light and flashy fuels were abundant and twice as tall and thick as in normal years

- Moderate to heavy fuels (brush and oak woodland) were extremely dry and abundant

- Some homes did not have adequate clearance of native vegetation around the structures

- Many homes had good clearance from native vegetation, but were surrounded by combustible ornamental shrubbery which also contributed to the fire spread into structures

- Predominate fuel was grass, brush, and oak woodland which can send heavy embers skyward

- Oak trees, palm trees, and conifer trees will send burning material high up into the convection column and those hot embers can rain down causing new spot fires ahead of the main fire

- During the autumn months, oak leaves fall off trees adding to the combustible ground litter which can contribute to ember storms (similar to last year’s Gatlinburg Fires)

- In some cases, ornamental shrubbery planted around homes appeared to have been well irrigated, causing some plants and trees to survive while homes burned

Topography

The areas where the fires were burning are mountainous, fairly hilly and in some cases steep and rugged. Most drainages on the west side of the mountain ranges in the area are in perfect alignment for a northeast wind to send the fires down into the valley areas to the southwest and into populated, urban, and commercial areas. Many homes were built along ridgetops and in canyons and passes adjacent to heavily wooded areas.

Digital Globe Imagery released October 14th, 2017 shows whole neighborhoods wiped out in northeast Santa Rosa by the Tubbs Fire.

National Fire Danger Rating System

NFDRS components were at the extreme and very critical levels with the Energy Release Components (ERCs) at the highest levels we have seen in the past 26 years (since ERCs have been monitored). The ERCs for these fires were greater than 90%. ERCs relate to the available energy (BTUs) per unit area (square foot) within the flaming front at the head of a fire. Daily variations in ERCs are due to changes in moisture content of the various fuels present, both live and dead. So this number represents the potential heat release per unit area in the flaming zone. As live fuels cure and dead fuels dry, the ERC values get higher, providing a good reflection of drought conditions. Ignition Components (IC) were hovering between 90% and 100%. The IC numbers represent an estimate of the probability of ignition when embers are blown in the wind ahead of the main fire and are able to contact a receptive fuel bed, then each could result in a new fire. An IC of 90% to 100% means that if 100 embers are blown in the wind and come in contact with a receptive fuel bed, than those embers will result in 90 to 100 new starts (spot fires). Scientific research is showing that many of the above factors can be attributed to Climate Change or Global Warming.

Multiple Fires and Lack of Available Resources

Multiple fires ignited during an extreme wind event, resulting in fifteen major fires burning at one time in Napa, Sonoma, Mendocino, and Solano Counties. This quickly overwhelmed local, State, and Federal firefighting resources that would normally be available to respond mutual aid to the area where the fires were burning. The first fire (Tubbs) along Tubbs Lane near Calistoga was ignited at about 2230 hours on Sunday night and began burning rapidly to the southwest towards Santa Rosa. As more fires ignited, many resources that were originally responding to the Tubbs Fire were diverted to other new fires. This trend continued for almost twelve hours, resulting in insufficient resources being assigned to active fires burning in the North Bay, while other in-state and out-of-state resources began responding for mutual aid, but had long travel times. At the same time, other major fires were igniting, one in Orange County and two in Butte County, further taxing the State’s Master Mutual Aid system. The causes for these fires are still under investigation and have not been released, but rumor has it that downed powerlines, downed power poles, and downed trees into powerlines were largely responsible for causing several of the fires.

Ember Storms

Abundant light, flashy, heavy, and ground litter fuels (dead leaves off of trees, etc.) coupled with the very high winds began blowing burning embers into receptive fuel beds. This phenomenon was definitely a major contributor to the rapid fire spread, creating spotting. Many homes and commercial structures had combustible materials next to and in close proximity to the structures, allowing the many spot fires created by embers to spread into those structures.

Rapid Evacuations

The majority of the fires were ignited at nighttime or in the early morning hours, catching people asleep and in their beds. In many cases the fires were rapidly encroaching on structures when people were awakened and made aware of the hazard, causing many people to evacuate with only the clothes they were wearing and without closing some doors, windows, garage doors, etc. This left homes more susceptible to ember intrusion, causing some homes to burn from the inside out.

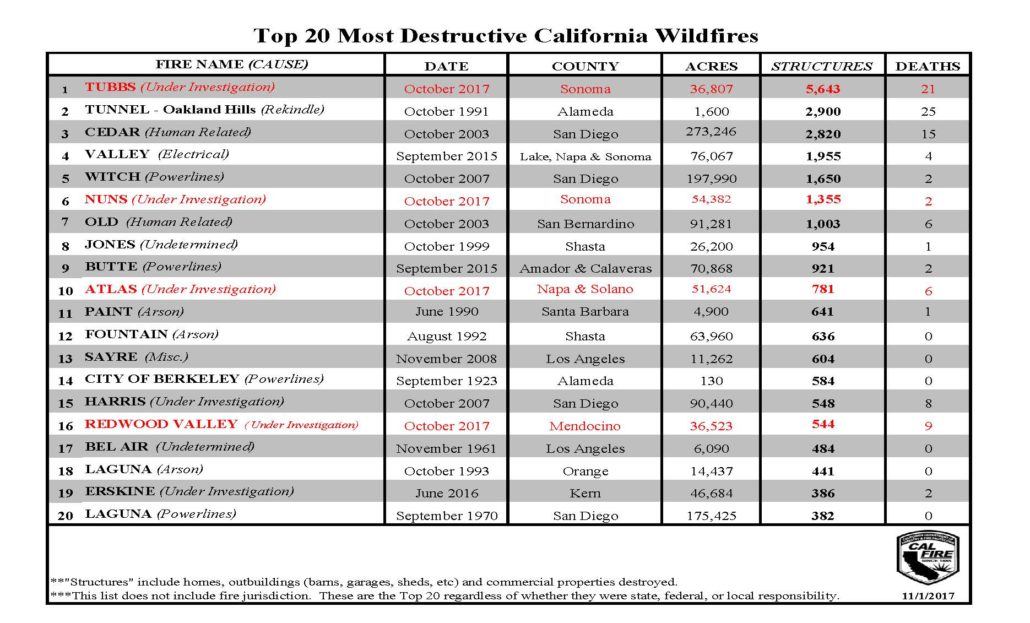

An updated (Nov 1, 2017) look at California’s 20 most destructive wildfires with four fires added (in red) from last month’s Napa Sonoma fire siege.

Written by: Douglas J. Lannon, Senior Fire Liaison, RedZone Disaster Intelligence, LLC.

3 Comments