© 2017 Sony Pictures Digital Productions Inc. All rights reserved.

Motion Picture © 2017 No Exit Film, LLC. All rights reserved.

2017 has brought devastating wildfires to much of the Western United States. Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington all fared way worse than expected with more than 8 million acres consumed and hundreds of homes lost. California was the hardest hit, experiencing the deadliest and most destructive fires in the state’s history. The fires that tore through Northern California last month engulfed over 245,000 acres, destroyed some 8,000 structures, and caused the loss of life to more than 40 people. Much of country is fortunate to not experience wildfires of this scale and may find this level of devastation hard to comprehend. Fewer still understand the hard fought battle wildland firefighters wage to protect land, life, and structures.

No films in recent memory have told a compelling story of the unsung heroes of wildland firefighting. Short of news stories, audiences likely have little appreciation for the fury of a large wildfires moving like a tidal wave across the landscape. Most of the recent firefighting movies have focused on urban fire stations or have been laughable action films like Firestorm. In the wake of the historic 2017 wildfire season a movie now in theaters finally helps remedy that.

Only the Brave released by Columbia/Sony Pictures recounts the tale of a small group of wildland firefighters, the Granite Mountain Hotshots. The movie, based on an article in GQ titled No Exit, by Sean Flynn, focuses on the personal struggles of Superintendent Eric Marsh (Josh Brolin) and Brendan McDonough (Miles Teller), whose personal dramas act as a back drop to the formation of the Granite Mountain hotshots and the fires they battled across the country.

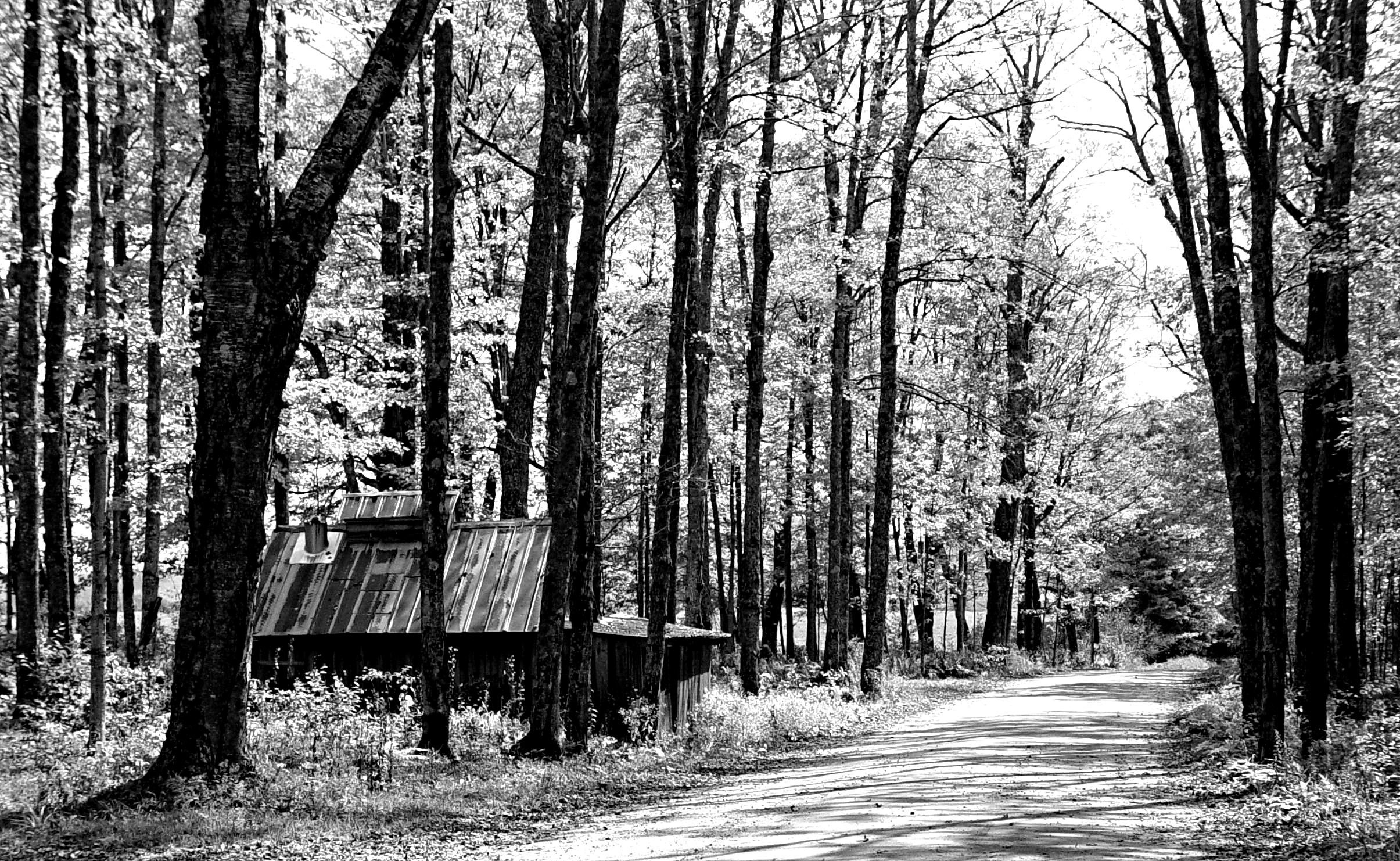

The Granite Mountain Hotshots started as a fuels mitigation crew for the city of Prescott before transitioning to a type 2 hand crew in 2004. After becoming frustrated about the crew’s role on numerous fires, Marsh fought for the team to earn an evaluation to become certified as a Hotshot crew. In 2008, after a lot of hard work and politicking the crew earned the distinction as the first municipal hotshot crew in the nation. Hotshots are small crews of elite wildland firefighters trained to fight fires directly in remote backcountry terrain with shovels, chainsaws, and limited support from other resources. Often working in steep rugged terrain with hot and dry conditions, they dig line, cut down trees and light back fires to help keep contain fires to a planned perimeter.

The first two thirds of the movie unfold around these events showing the arduous training, inherent dangers of firefighting, and the bonds it forms within the crew. Much of the story is told through the perspective of new recruit Brendan McDonough, a recovering drug addict who is given a second chance to build a new life for himself and his new born daughter. McDonough’s training allows the movie to tell a story that is not only engaging but is also informative and instructional.

Numerous scenes in the movie depict the crew digging line, clearing brush, and using drip torches and flares to start fires. Seeing firefighters using fire to fight fire is likely new to audiences inexperienced with wildland fire-fighting techniques. The movie shows how flares and drip torches allow firefighters to burn vegetation ahead of an incoming fire-front in order to establish a fire break that robs the approaching blaze of fuel that it needs to continue spreading. These fires can also be used to help steer the main fire or provide safety zones.

The film seamlessly blends some intense scenes of the crew with amazing special effects to highlight the enormity of wildfires and the challenges faced in trying to contain them. The director Joseph Kosinski avoids the normal pitfalls inherent in the typical macho-posturing movies and instead delivers a poignant story that is both emotional and respectful. Kosinski and the actors deliver a sincere portrayal of their real life counterparts along with their authentic camaraderie. Although there are some obvious Hollywood liberties taken, the film faithfully recreates the facts that matter most. Some of the scenes, like the human pyramid in front of the giant Juniper, were painstakingly recreated to pay homage to the now iconic photo of the crew celebrating the successful saving of the sacred Prescott tree during the Doce Fire.

I was refreshing to see that even as the film builds to its inevitable climax at Yarnell Hill, it stayed true to the story, adhering closely to official reports. For example, much of the dialogue is pulled straight from radio transcripts and the accounts from other firefighters on scene. Kosinki lays out the events of the Yarnell Hill Fire “as is” without attempting to try and invent motivations or answer questions that remain unanswered. The result is powerful and effective.

Only the Brave should give viewers a greater appreciation for the role played and the danger faced by wildland firefighters in the perennial battle to protect lives and land in the American West.

The Granite Mountain Fund drives donations to support firefighting as well as the towns and families connected to and impacted by hotshots and their work.